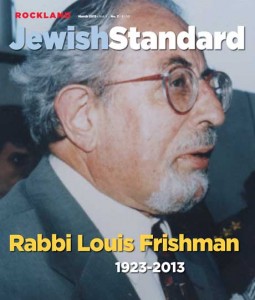

Community mourns passing of Rabbi Louis Frishman

Rabbi Louis Frishman, who came to Spring Valley in 1951 and built a small 150-member Reform congregation focused on social action and community involvement into a 900-member synagogue with a waiting list, died on Feb. 6 after a long illness. He was 89.

Rabbi Louis Frishman, who came to Spring Valley in 1951 and built a small 150-member Reform congregation focused on social action and community involvement into a 900-member synagogue with a waiting list, died on Feb. 6 after a long illness. He was 89.

He inspired his congregants to get involved in the community. He ruled Temple Beth El in a firm, but loving style, making certain that the work he thought needed to be done — whether educational, philanthropic, artistic, or activist — happened. A man of action, he believed in leading by example, even if that meant waking up to serve breakfast to the poor at 6 a.m.

He took scores of teenagers from his confirmation classes to Poland and Israel — long before there were such programs as March of the Living and Birthright Israel — so they could see what Nazi Germany’s war on the Jews had wrought, and the powerful promise of Jewish rebirth that was embodied in the State of Israel.

Although he retired from Temple Beth El in 1994, he continued to be engaged as rabbi emeritus. Known to his congregants simply as “Rabbi” with no surname, his death represented a palpable shift, coming at a time when the congregation, now surrounded by Orthodox institutions, is considering a merger with a New City Reform congregation.

“He was quite large, but he wasn’t intimidating,” said David Sternlicht, who attended confirmation classes in 1980 and was one of Frishman’s “Temple Kids.”

“When he spoke, you listened,” said Sternlicht. “He was very persuasive, and he would always speak about the issues of the day.

“He looked the way a rabbi should look. I don’t think they make those anymore. He is the end of an era.”

Frishman worked for the freedom Soviet Jewry, supported Israel, and involved his congregants in caring for those in the community at large. He also was present in his congregants’ lives, often setting them on paths that would shape their futures.

Steve Rosenzweig’s family joined Temple Beth El in 1949, two years prior to Frishman’s hiring. The families became close. Rosenzweig recalled playing basketball at the Frishman home. He also remembered “always being in trouble at Hebrew school,” even though “Rabbi” knew how to keep the kids in line.

“He was a tough rabbi; he made us tow the line,” said Rosenzweig, a past president of JCC Rockland and current president of the Rockland Jewish Community Campus. “It really developed us, and to this day we talk about it.”

Once at synagogue, Rosenzweig, then about 30 years old, remembered Frishman giving him a look and then saying, “Steve, I want to see you after services,” that put Rosenzweig in mind of those “being in trouble” days. Not having any idea what he was in for, Rosenzweig was surprised that Frishman wanted to appoint him as the synagogue’s liaison to the local UJA, which is today the Jewish Federation of Rockland County.

“I thought I was a big deal if I gave $25 to the synagogue,” said Rosenzweig. “What did I know? When he appointed me, it just started me on the road to what I do today.”

What people recall was Frishman’s ability to motivate his congregants to be committed to a broader Jewish and social justice vision, along with his love of fine art, Jewish thought, and a desire to push boundaries.

“His activism was profound,” said Rabbi Ronald Mass, who came to Beth El as an assistant rabbi in 1984, and later became its spiritual leader when Frishman retired. “He really came out of that prophetic vision. He was not afraid to speak his mind, and express his principals and core beliefs.”

He got his hands dirty

Rabbi Louis Frishman was born in Denver on Oct. 12, 1923, to Hanna and Harry Frishman, recent immigrants to the United States. His father, who ran a variety of small businesses, including a boarding house, died when he was five years old. His mother, who had a good head for business, raised Frishman and his two brothers — Nate, who was born in Poland, and Jack, two years younger — on her own.

They attended a local Orthodox synagogue where Rabbi Manuel Laderman became his mentor and a father figure to him. At 14, Frishman left Denver to attend a yeshivah in Chicago. Shortly after, he also enrolled in the University of Chicago, where his “eyes became opened to other things,” according to his wife, Mimi Frishman.

Respectful of Jewish tradition, but fired up by his university learning, the rabbi decided to seek ordination from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. While there, he met Mimi Mandel, a student of the College of Conservatory of Music, in a doctor’s office. He was there for a mastoidectomy, and she was “a singer with a sore throat,” she said.

He pestered the doctor for her number, who told Frishman not to go out with her, that the “conservatory students are nuts,” said Mimi.

He ignored the good doctor’s advice, perhaps exhibiting the independent thinking he later became known for in his rabbinate. The couple were married on Thanksgiving in 1950 and the following year they moved to Spring Valley, to help steer a fledgling Reform congregation, Temple Beth El. They began a family, with Judith, their first daughter, arriving in 1953, followed by Deborah in 1955, and Marcie in 1959. Unusual in a Reform-affiliated family, all three attended what was then called the Hebrew Institute of Rockland, an Orthodox school that was later renamed ASHAR.

Housed in a small building at Jackson Street and Furman Place, Temple Beth El had 140 families as members. The Tappan Zee Bridge had not yet been built, and Rockland County was a sleepy backwater, a country place of farms and summer bungalow colonies. Yet within a few years, Beth El had more than 400 families. Once the bridge opened, families poured out of the Bronx and Manhattan to settle “upstate.”

“Not all of them had been brought up in a Reform background,” said Judith Frishman, the first chair for Jewish Studies at Leiden University in the Netherlands. Many had little or no Jewish background, as well. As the congregation grew, Frishman had to “read the congregation to adjust his message,” his daughter said.

He read it well, and was good with young people.

It was the early 1960s. Dissent over United States involvement in the Vietnam war was growing, and the Civil Rights movement was in full swing. Frishman had causes to champion and he brought his congregation along for the ride.

In 1965, the congregation moved to its present location on Viola Road and grew to 900 families, with a waiting list of more than 100. As it grew, he helped launch new Reform congregations Beth Am Temple in Pearl River, Temple Beth Torah in Nyack, Temple Beth Sholom in New City, and the Reform Temple of Suffern, which has since merged with a New Jersey congregation and moved.

In the case of Beth Am, a few dozen families in Pearl River wanted to join Beth El, and Frishman, in his “inimitable style, knowing he had a multi-year waiting list for membership said, ‘Why don’t you start your own congregation in Pearl River?” according to Rabbi Daniel Pernick, who has led Beth Am for 28 years.

“He was smart on the micro and the macro level,” said Pernick. “[Beth El] wasn’t just growing, it was burgeoning; they couldn’t hold all the people who wanted to go there. And it was saying we should have more than one congregation. He was definitely a major factor in getting our place started.”

With his young daughters in tow, Frishman took congregants to marches on Washington, D.C., championing civil rights. And in the late 1960s and early 1970s, he focused his activism on Soviet Jewry, partnering with then Rep. Edward I. Koch, who died on Feb. 1, in initiating the Soviet Jewry Relief Act. The bill passed, allowing the United States to lift quotas that enabled 100,000 Soviet Jews to enter this country.

The plight of Jews behind the Iron Curtain motivated the congregation to become the first in Rockland County to hold b’nai mitzvah ceremonies that had the participant “twin” with a child in the Soviet Union. In 1980, Ellyne Landin didn’t want to have a bat mitzvah, but her mother, Carol, had heard of a Long Island congregation where a proxy bat mitzvah had been held at the same time as one for a congregant, raising greater awareness of the religious restrictions and hardships Jews faced in what was then the Soviet Union.

“I asked Ellyne, ‘How would you like to have a bat mitzvah for a Russian kid who can’t?’” Landin recalled. Ellyne agreed, studied, and became a bat mitzvah along with Alina Kassin. After that, everyone at the congregation wanted to twin with a child in the U.S.S.R., she said.

“Rabbi calls me and says, ‘Everybody thinks this is wonderful, everybody wants to do this with their kids. Okay, you’re in charge,” said Landin, who now lives in Boynton Beach, Fla. “This went on for years.”

When the Soviet Union finally collapsed in 1991, Frishman informed the congregation they were adopting a Russian émigré family, providing them with an apartment, furniture, and a place to worship.

“He was a phenomenal leader,” said Landin. “He didn’t’ say, ‘Okay, you do and I’ll sit and wash my hands.’ His hands were just as dirty as ours. He would come to the rallies and protests….He wanted people to do, so he did.”

His causes involved those far away and close to home. According to family members, he assisted with helping the Skverer chasidim establish New Square in 1954. “As a Reform rabbi, he felt that they had a right to their community,” said Mimi Frishman.

But it was a program to feed the hungry, the Rockland Interfaith Breakfast Program, that got him out of bed at 6 a.m. on Sundays to serve eggs and coffee to the less fortunate of the county.

There he worked closely with Sister Barbara Lenniger, a Dominican nun, who found in Frishman a funny and warm spiritual compatriot. They worked together on a variety of projects, including raising local awareness about the need for affordable housing.

At one presentation, a group that helped potential homeowners build their own homes, presented some of their literature that required a signature. It cited a need to believe in Jesus Christ, Lenniger said.

“I turned to Lou and said, ‘I don’t know if you can do this,” she recalled. “And he said, ‘Well, if we can get affordable housing, I’ll sign anything.’

“He was always right on target,” she added. “He could always get to the crux of the matter about our ideals.”

Pushing boundaries

Frishman was not afraid to court controversy in ritual life, either. In 1967, Temples Beth El and Beth Sholom co-hosted a contemporary Friday night service that featured, “three dancers, two singers, electronic music, film projections, eerie soundtracks, psychodelicacies and [musician] John Cage in the pulpit,” according to The New York Times, which covered the “Jewish Happening.”

According to the Milken Archive of Jewish Music, Frishman’s reaction was enthusiastic, “I feel that electronic music is something that must be brought into the synagogue,” he was quoted afterward. “A service such as this also makes people reinterpret the words of the service.”

That desire to push boundaries extended to politics, as well. In 1995, as president of the New York Board of Rabbis, Frishman and a delegation of five other rabbis met with Yasser Arafat in Gaza as part of a two-day “peace mission” under the auspices of the International Committee on Peace in the Middle East.

Quoted at the time in the Rockland Jewish Reporter, Frishman said, “People change. [Former Prime Minister Menachem] Begin was a terrorist. [His successor Yitzchak] Shamir was part of the underground movement. But that’s how you build a nation. There’s an internal war on between the PLO and Hamas, just as there was between the Sternists and the Haganah.”

His love of contemporary art was well known and on Tuesdays, his day off, he would often take his daughters into the city to gallery hop and visit museums. It was a treat that made up for times when a rabbi’s busy schedule kept him from attending piano recitals and parts of vacation, according to Marcie Frishman, an ethnomusicologist.

His bookshelves include Jewish texts along with volumes on contemporary artists such as David Hockney, Henri Matisse, Alexander Calder and Bauhaus style. His love of art extended to Beth El, too, and when it was built, Frishman took a personal interest in the building plans and design.

Frishman’s impact went beyond his synagogue and beyond the Reform community, said Rabbi Henry Sosland, rabbi emeritus of New City Jewish Center.

“He had a wonderful sense of humor and little tolerance for anything that wasn’t genuine,” said Sosland, who as the first rabbi hired at the Conservative New City Jewish Center, was also building a congregation at a time when the Jewish population in the county was growing rapidly.

Frishman, he said, reached out to clergy off all sorts, including Msgr. James Cox and Orthodox Rabbi Moshe Kranzler of Haverstraw.

“I think there is a tendency for all our communities to become focused on our particular needs and to lose sight of the whole community,” Sosland said. “I think Rabbi Frishman tended to draw the various groups together.”

When the Soslands lived in Israel from 1969-1970, the Frishmans overlapped for half a year in Jerusalem. The two couples spent time together.

“He was just a wonderful person; personally we are going to miss him, because of his kindness and his perception of what was happening within the county in terms of the Jewish community,” Sosland said.

Although Frishman retired as head rabbi of Beth El in 1994, he remained an active member of the community. He continued to serve as chaplain at Helen Hayes Hospital in Haverstraw, where he served for more than 50 years. He also served as the first Jewish chaplain at the Spring Valley Fire Department. He helped found the Rockland Family Shelter in 1985, at a time when few clergy were speaking about domestic violence.

In 1976, he received an honorary degree from HUC. At the graduation ceremony, he joined his wife, Mimi, who had returned to school and graduated as the second woman cantor from that institution.

His niece, Rabbi Elyse Frishman at the Barnert Temple in Franklin Lakes, N.J., said that because he sent his daughter, Deborah, to the Union of Reform Judaism’s Eisner Camp, she too went, setting her on a path to become a rabbi and one dedicated to social action, not unlike her uncle.

“He created the opportunities for me to engage in the Jewish event that ultimately led me to be a rabbi,” said Elyse Frishman, who was recently detained for praying at the Kotel while wearing a tallit. “I was so moved by him. In addition to his passion for Judaism, there was this extra passion for social justice.”

As he became increasingly ill, he was hospitalized. There, even as a patient, he charmed everyone around him, according to Mimi, offering advice and counsel, just as he had done as a pulpit rabbi. Whenever she visited, though, there was one thing he always wanted to know:

“Tell me what’s going on at temple,” she said. “What’s going on at temple?”

Frishman is survived by his wife, Mimi, his daughter Judith and son-in-law Edward Van Voolen, daughter Deborah and her husband Richard Siegel, and daughter Marcie, his brother Jack, and four of grandchildren.